- The Library of Babel

- Posts

- Being a Feminist in Antiquity Meant Rejecting the World (and God with it)

Being a Feminist in Antiquity Meant Rejecting the World (and God with it)

According to the Gnostics, it was actually a good thing that Eve got us all expelled from the Garden

In 1945, an Egyptian man named Muhammad Ali of the al-Samman clan was riding his camel alongside several fellahin near the city of Nag Hammadi to gather natural fertilizers. While digging in the sand, Muhammad Ali's younger brother, Abu al-Magd, hit upon a clay jar. He tried to open it but soon gave up, so his older brother Muhammad took over.

Muhammad initially feared that the jar might contain a jinn, but as he told scholar James M. Robinson years later, his love of gold overcame any fear of evil demons. He did not find gold in the jar—its lid now broken by him—but instead a collection of old books he wasn't sure what to do with.

Thanks to the quick-wittedness of that man, what he found on that particular day and the fact that he saved it from oblivion changed the way we look at the history of religion in the West, our views about early Christian history, and—what I'd like to explore in this essay—what it means to be "feminist" in the ancient world.

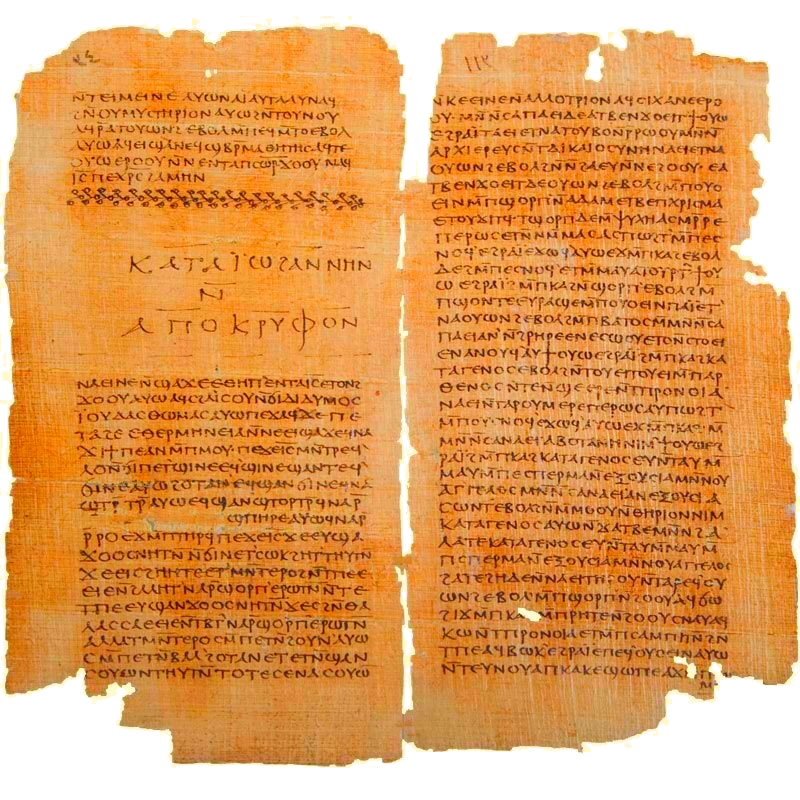

Codex II, one of the most prominent Gnostic writings found in the Nag Hammadi library, which contains the end of the Gospel of Thomas and the beginning of the Apocryphon of John

Not long ago, I came across a meme that stayed with me much longer than memes typically do. Though I couldn't track it down, I remember it was about the problematic lesson we get from reading the creation of Man in Genesis—originally (we are being told), it was Adam, a man, who begat a woman, not the other way around. It's as if the Bible tells us that men give life, not women.

Reading it, I was instantly reminded of a passage in one of the ancient and very strange texts found by Muhammad Ali al-Samman in the cliffs near Nag Hammadi. When translated to English from the Coptic language, the title of it is "The Nature of the Rulers." It purports to tell exactly that: the hidden nature of the rulers of this world, the evil Demiurge, and his army of officers/angels known as the Archons.

Reading it for the first time, you get a sense that what you are being told—is not so much the "behind the scenes" version of Genesis—but a completely different and contradictory retelling of that story of creation.

In what I consider to be nothing short of a revolutionary passage, Adam wakes up from a sleep induced by the God of the Hebrew Bible to find Eve by his side. Though in the biblical story Eve was created by God from Adam's rib, that is not the case here.

In this retelling of the familiar story, Adam turns to Eve to say:

You have given me life. You will be called the Mother of the living.

For she is my mother.

She is physician,

woman,

one who has given birth. (89:14-17)

While this might seem like a strange point to obsess over, it's hard to express how radical and far-reaching this riff on the Genesis story is. There were countless retellings of the biblical narrative circulating in the ancient world, but as far as I know, the Gnostics are the only Christian sect who saw Eve as the hero.

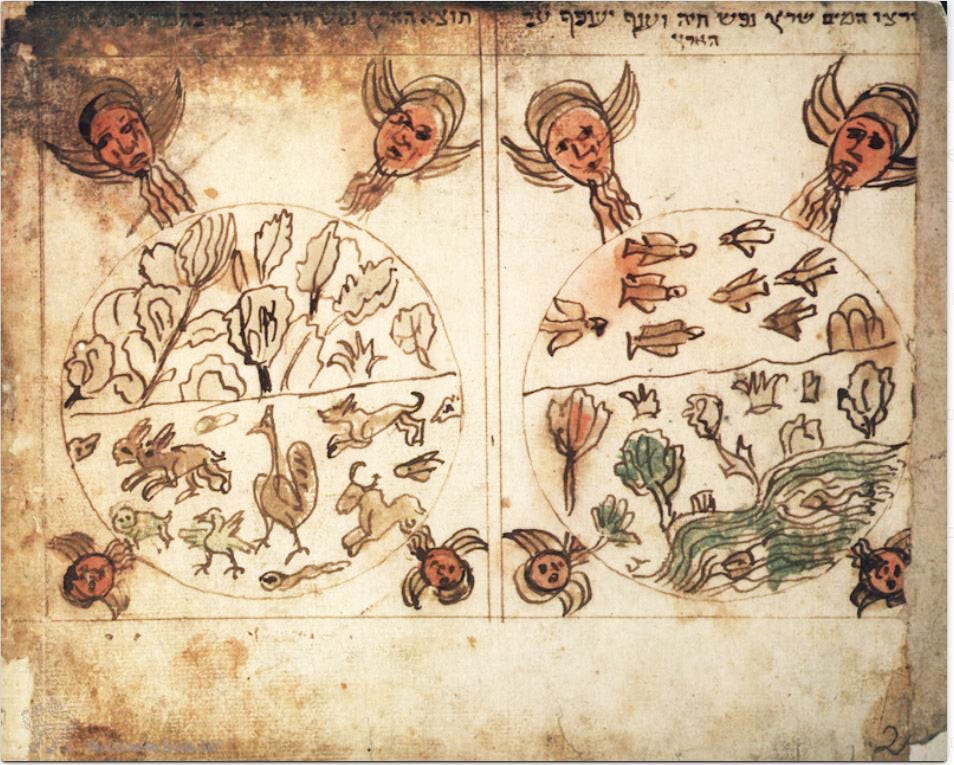

Adam and Eve in the Jewish manuscript known as the “Sarajevo Haggadah"

Remember I told you that the discovery of the texts inside the mysterious jar in Nag Hammadi changed 'our views about early Christian history'? This is because, for the first time in history, we could read the texts of a group (or groups) of Christian believers who were known to us as the Gnostics.

Gnosis, the Greek word that the Gnostics are named after, is a term coined by none other than Plato. According to the ancient Greek philosopher, Gnosis is a type of knowledge that comes from experience, as opposed to intellectual learning. By the time the word came to be used by the so-called Gnostics (a name given to them by their enemies), it had evolved to mean secret knowledge that could potentially lead to salvation.

And what, you might ask, did the Gnostics know that no one else did? The truth of this world and who is behind it.

When reading the Christian and Hebrew Bible, one might develop a sense of understanding about the divine nature of reality—about God and His plan for us, the chosen people, and the Messiah. However, for the Gnostics, all of this is regarded as an elaborate lie.

In “The Secret Book of John”, another of the Gnostic texts found in Nag Hammadi, we encounter the true God—a far higher and greater being than the one we know from traditional scriptures. This is not the God of the Bible but a great and vast mind, whose divine thoughts are called eons—divine beings that emanate from Him.

According to the Gnostics, the God we thought we knew, the one portrayed in the Christian and Hebrew Bible, is not the true God but an evil and delusional being of lesser order. To denigrate this lesser being, the Gnostics referred to him as the Demiurge. This term, originally from Plato's dialogue Timaeus to denote an artisan-like figure, was transformed in Gnostic thought into a blind and foolish creator.

Essentially, what we have here is one of the first conspiracy theories of the ancient world—certainly one of the most influential. A cabal of evil beings pulling the strings without our knowledge. The conspiracy is so well-organized that the chief conspirator made us believe he is the good guy—a god, the only God in existence.

The Gnostics viewed our world, the chief creation of the Demiurge, as an imperfect and corrupt version of the true divine realm. Ours is a realm of matter and flesh, but in the true realm of God, there is no matter, just spiritual essence.

It is only after understanding this fact that we can begin to grasp how radical the Gnostic vision was. In The Nature of the Rulers, we learn that spiritual Eve—who was separated from the body of Adam—tried to warn him about the nature of the evil god. She attempted to tell Adam that the Demiurge created humanity to worship him and boost his blind ego.

As creations of the lower archons—the evil god and his band of angels—humanity is supposed to be an imitation of lesser forms, a copy of a copy in a sense. However, this is only half true. The Demiurge and his archons did create man and woman in their image, but crucially for our salvation, also “after the image of God that had appeared in the water”—the image of the Goddess Incorruptibility, one of the higher eons. Our human bodies might be corrupt, but not so for our divine soul.

Creation of the world in the “Warsaw Bible”

When the archons saw spiritual Eve beside the awakening Adam, they were filled with lust towards her and tried to rape her. She escaped to the higher realm by turning into a tree. When the higher spirit that filled Eve vanished, only a shadow remained, and that shadow—the physical Eve—was violated by the archons. In 'The Secret Book of John,' the consequence of this rape is the birth of Cain and Abel.

But the 'female spiritual presence,' as it is called in The Nature of the Rulers, the presence that was the spiritual Eve, did not leave humanity to their fate. Instead, she came back in the form of a serpent and, controlling that creature, instructed (not seduced) Adam and 'the woman of flesh' (meaning the human Eve) to eat the fruit of the Tree of Good and Evil.

Even now, while she is no longer a divine being in a human body but a 'regular' woman, it is Eve who first ate from the fruit and then gave it to her husband. When the archons discovered that, they cast Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden.

Those of us who grew up with the traditional telling of the story of Adam and Eve obviously find the Gnostic retelling to be foreign, even strange at times. But the more I read it, the more I'm convinced that this 'new' retelling could actually solve many of the questions that two millennia of traditional interpretation could not.

Why did God put a tree in the middle of the Garden of Eden, abounding with seductive fruits, and then forbid two humans who are basically mentally children from eating it? What kind of a test is that? And why should that first transgression—'Mans First Disobedience,' as John Milton called it in the first line of his epic poem—be the reason we all suffer to this day?

The answer according to the Gnostics is simple: The god who cast us from the Garden is evil, and even more importantly—it was all part of the higher God's plan of salvation.

It wasn't some test that led God to place the tree of knowledge of good and evil at the center of the garden—a test that He, the all-knowing God, knew Adam and Eve would fail. According to the Gnostic text, the rulers of this world commanded Adam not to eat from the fruit of the forbidden tree because of the true God. It was He who made them, without their knowledge, warn Adam and Eve not to eat from that fruit, thereby actually hinting to them that they should eat it and gain knowledge of their true situation.

I believe the same is true of Adam and Eve being cast from the Garden.

The rulers threw humanity into great confusion and a life of toil, so that their people might be preoccupied with things of the world and not have time to be occupied with the holy Spirit.

In the Gnostic myth, our life after the fall is less a punishment for defying God and much more about being a sorrowful distraction preventing us from reaching the truth. And yet, the Gnostics tell us that we shouldn't despair.

The reality of human life might seem hopeless, but the real God has a plan: which is “To bring all into union with the light.” And until the coming of Jesus—the final savior of humanity—the execution of God's plan rests mainly on women: Eve and her even more impressive daughter, Norea.

The rest of the story in The Nature of the Rulers focuses on Norea, the daughter of Adam and Eve, and her battle with the archons who try to abuse her as well. This time they fail, and the Angel who comes to her assistance tells her the true story of creation and humanity's future salvation with the coming of the Perfect Human—Jesus, who is not named in the text.

This is the earliest picture of the Last Supper to survive till our time. it was made in Italy in the 6th century, and is a part of a manuscript named St Augustine Gospels.

How ‘Feminist’ were the Gnostics anyway?

A historian whose class I attended in college once told the class that the biggest revolution of the 20th century is the Feminist revolution. The idea that men and women are equals is one statement that goes against Western thought itself. While we might find the germs of this idea in Greek mythology, particularly in the existence of powerful goddesses, when it came to the human realm, it was Penelope wife of Odysseus, who waited 20 years for her Husband-King to return from his travels while enduring harassment from haughty suitors.

For most of Western history, women were considered another form or category of property, transferred from father (or older brother) to husband upon coming of age—often at shockingly young ages by modern standards. Many times, the bride didn't have much or anything to say in the matter, nor did her teenage-ish groom.

In this essay, I use the term 'feminism' not in its proper dictionary definition. We're not talking about actual feminist ideas that have any relation to the movements we're familiar with in the 20th century. We're not even talking about something that can be called proto-feminism. What I'm referring to is an idea, not explicitly formulated in Gnostic texts, that men and women might be seen as equals. This revolutionary notion is something I believe the Gnostics came close to expressing in some of their texts.

There exists what I consider a flawed version of feminism, a call to reject men and see them as a danger to women's liberation. At its extreme, it can manifest as viewing men as inferior to women. This view, overly exaggerated in chauvinist circles as if it's the basic feminist view of the world (which, of course, it's not), is also a view that the Gnostic texts we discussed took into account before rejecting it altogether. In the Gnostic myth no part is superior to another—the female or the male. They should coexist in harmony, a word we find emphasized time and time again in Gnostic creation stories.

We find this important lesson crystallized in the workings of Sophia, the goddess of wisdom. After the emanation of various eons from the origin God, Sophia decided to create a being without the help or consent of the other eons. It is her action that led to the birth of the false God, the Demiurge, which the Gnostics see as the God of the Hebrew Bible, residing in an inferior material realm and seeing himself as the only true God in his blind universe.

The lesson is clear: even the female, the mother of all, cannot create true and good things without being in harmony with the male.

As for the actual flesh-and-blood Gnostics, the people who wrote and believed in the worldview of the texts found in Nag Hammadi—how feminist were they?

The short answer is that we don't know. When dealing with a topic as complicated as this, we need to remember that we don't really know who the Gnostics were, and the texts of Nag Hammadi, along with the highly problematic testimonies of their enemies, the proto-orthodox Christians (the sect that won out in the end), are all we have to go on.

But we can say that all societies accept and even live peacefully with various levels of hypocrisy in their day-to-day operations. It is perfectly possible to hold certain values as sacred and still live in ways that are contradictory to them. Which means that the male Gnostics might have treated their women as poorly as the rest of the world around them, or not.

The Medieval Church placed Mary right alongside her son as an object of prayer and worship—and that didn't change the attitude towards medieval women of the time. In fact, one could make the opposite argument and claim that actual flesh-and-blood women automatically lost to a perfectly idolized woman, the mother of Christ.

So, we might want to ask a different question, one that we can answer with better accuracy: How 'feminist’ are the Gnostic texts? In my humble opinion, more so than most other texts we'll encounter for the next millennia and a half, probably.