- The Library of Babel

- Posts

- Why I'd actually prefer to be sent to the first circle of hell than to heaven

Why I'd actually prefer to be sent to the first circle of hell than to heaven

In praise of Limbo, because not all circles of hell were created alike

Near the end of his life, William Blake turned to study The Divine Comedy. Similar to what he did with John Milton's epic poem on the fall of mankind from grace, the visionary poet and artist didn't plan to limit himself to 'just' reading Dante's great journey to the lands of the dead. Blake wanted to be inspired by it, to communicate with it using the best means he had at his disposal: his art.

Blake created 102 watercolor paintings of The Divine Comedy. He planned to finish them all and probably to add more to them but died before he could finish even four of them.

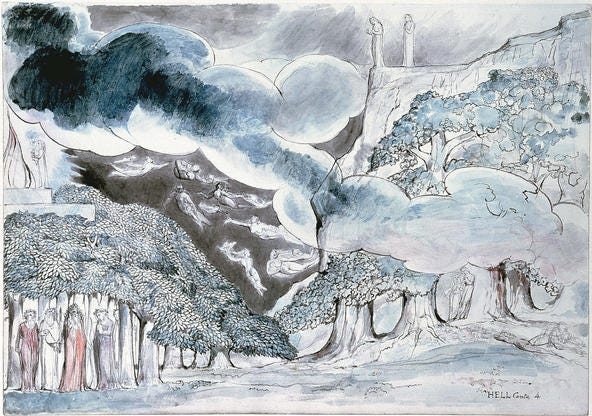

One of these unfinished paintings, which looks more like a sketch, details the first circle of hell. While most of Blake's depictions of the other eight circles of hell are much more elaborate, I find this work to be especially interesting. Blake manages to capture a nostalgic quality that permeates the (after)lives of all who are found there. And yet, after reading Canto IV of the Comedia, I can't help but look at the scene with a bit of jealousy. It's a strange feeling (I know) that I'll dedicate this essay to explaining.

Homer and the Ancient Poets in the First Circle of Hell (Limbo)

Midway along the journey of our life, I awoke to find myself in a dark wood.

Simply uttering the name Dante is enough to conjure up terrible scenes of suffering and horror. In the first of three parts of Dante Alighieri's great poem, The Divine Comedy, the 13th-century Florentine poet achieved an almost unbelievable feat: depicting the Inferno, the Christian hell, in harrowing and detailed poetic description.

In the 33 Cantos of the Inferno, we encounter, among many others, a man who carries his severed head as others might carry a lamp; two lovers who were swept by uncontrollable passion in life but are now whirled and swept by an unceasing storm; heretics who denied the existence of a soul and are buried in burning graves, while others, the traitors, drown in a frozen river. Every sin receives its metaphorical punishment in Dante's vision.

That is the principle of the Contrapasso. It is the one “law of nature” that applies to hell, stating that for every sinner's crime there must be an equal and fitting punishment.1

However, and this is crucial, not all circles of hell are created equal. In fact, for me at least, there is one that can even be considered attractive—a place I would rather go to, perhaps even preferring it to the possibility of entering Eden.

In episode 2 of "The Power of Myth," Joseph Campbell, the eminent scholar of myths, expressed this sentiment beautifully:

I think in heaven you’ll be having such a marvelous time looking at God that you won’t get your own experience at all. That’s not the place to have it. Here’s the place to have the experience.

In essence, what Campbell suggests is that we, the living, should cherish this world, for when we reach heaven, our focus will be consumed by raving about God's effervescent light. So fine, according to Dante, not all of us—indeed, most of us—will not reach Eden. But those who do will undoubtedly be engulfed in divine light. When Dante finally encounters God, he gazes upon the sun. This moment signifies the fulfillment of the longed-for goal toward which all Christian mystics strive: union with God and absorption in Him—the coveted 'Unio Mystica.'

Yet, there exists another possibility, reserved only for the greatest thinkers, poets, and writers in history—those unfortunate enough to have been born before the incarnation of the Son in the flesh, before the birth of Jesus.

This is the first circle of hell, the Limbo, described as a beautiful castle with seven walls that are surrounded by a small stream. It is the place where the virtuous pagans dwell, and where they, great thinkers and artists that they are, hold endless symposia. Who will not be found there? From Homer (which Dante never got to read because there was no Latin translation at the time), to Horace, Ovid, and Lucan – four of the greatest poets of the ancient world who praise Dante as a poet worthy to be counted among their ranks. Standing on a small hill, Dante recounts more of the great thinkers found in Limbo: Socrates, Plato, Cicero, Seneca, and "the master of those who know" (Aristotle). And also, a number of Muslim figures that Dante obviously respected, but did not think they deserved to go to Eden.

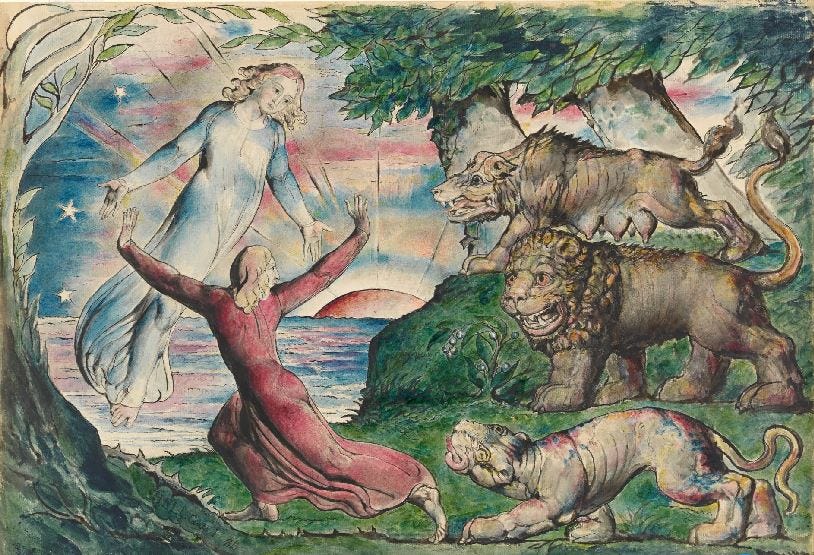

Dante running from the Three Beasts

In describing Limbo and listing the many names of the souls who reached it, Dante is playing a complex and interesting game here. He is keenly aware that the Christian civilization in which he resides was profoundly shaped by the preceding pagan civilizations—namely, the Greek and Roman cultures—that it, in a sense, conquered. Although he himself did not invent the idea of Limbo—the place where the people who did not sin but were not baptized (and this includes babies who died before baptism) were sent to after death—he developed this place into the ideal of the "Locus Amoenus", which in Latin means: the pleasant place.

Dante depicts Limbo as a castle surrounded by a meadow. All is lighted by an artificial light. It is not the true divine light, yet it is not a dark place as the hell to which Dante continues and descends. The people there, the "lost" according to the poem, yearn towards God. This is their sole torment. They are not punished beside. As Virgil tells Dante: "We live without hope, but only with desire".

At a first glance, this may seem unfair to us. Why would the souls who had not sinned in their lives, who actually possessed something of divine wisdom without necessarily knowing it, why would they be sent to a comfortable—very comfortable—version of hell but still hell non the last, instead of spending the rest of eternity in Eden? This is a valid question, but it overlooks a crucial aspect of the Christian worldview: it is only after death that we enter the realm of divine justice, where justice is absolute. According to Christian belief, only those who were baptized and sought repentance for their sins in life can enter Eden, likely after undergoing purification in Purgatory. We may not accept it, but that's how things happen.

The duality of holding deep respect and admiration for certain pagans, yet not deeming them worthy of God's grace, is not a contradiction that offends the Christian God in any way. Consider the lowest circle of hell, the ninth, at the center of which lies Lucifer—the Devil—feasting on his three arch-traitors in history. While the central head preys on Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus, the other two heads feast eternally on the two main conspirators in the assassination of Julius Caesar. This revelation is remarkable, as Caesar himself is consigned to Limbo.

Yet, there is no inherent contradiction in this arrangement. Although the Roman Empire in its inception may have been a pagan and sinful empire, its establishment was a central part of the divine plan. And the fact that the empire converted to Christianity with Constantine is conclusive proof of that.

Lucifer and his three heads

This holds true for the wisdom of Aristotle, Plato, and other Greek thinkers, as well as the poetry of Homer, Virgil, and other great poets of antiquity. Their works contain elements of Christian divine truth, and therefore it is "allowed" to be used even in the Christian era that eclipsed it.

Not all ancient philosophies align with this perspective. For instance, in Canto X, Dante vividly portrays the suffering of Epicureans in the sixth circle of hell, including one of Dante's personal hero—Farinata degli Uberti who saved Florence from destruction. The followers of the ancient Greek thinker Epicurus are punished because they denied the existence of the soul.

In this sense it is difficult to say that Dante Alighieri lived in the Middle Ages, the derogatory name given to the period of a thousand years between the Renaissance and Antiquity. Seeing the world through Christian eyes, Dante believed he was living in the truly reformed period. And even if the majority of humanity are still sinners—well, that's the way it has always been and probably will always be—the Christian gospel was given to mankind. Except for the first circle of the Inferno, all sinners sent to the "real" hell were sent there because they refused to atone for their sins while alive. And so, they continue to justify themselves after death. Most claim they don't understand what they did wrong, or—to be precise—they refuse to accept the fact that what they did was wrong.

Through his encounters with the souls of sinners, Dante's philosophy of sin is revealed. The sinner almost always knows that what he or she is doing is wrong - and here Dante is talking about all of us of course. The sinner knows that his or her actions are a violation of God's laws and his justice but does it despite this knowledge. Sin is not a matter of a lack knowledge, but of choice.

The fault of most of the souls in the first circle is that they were born before the Christian gospel, before the redemption of man through the incarnation of God in the flesh, before God sacrificed his son. They spend eternity pleasantly—away from God's light but without additional suffering—because, through their talent, high character, and sharp minds, they were able to grasp something of the divine truth. What they managed to comprehend was incomplete and imperfect, yet to this day (in Dante's time), the Christian world is helped and largely relies on their thoughts and actions.

And who is the guide that Dante chooses for himself in the realms of the dead? In hell and purgatory? Not a Christian saint, not even Paul, who descended into hell, but Virgil—a pagan Roman poet who readily admits upon meeting the Florentine poet that he never entered the heavenly city of the divine emperor. He did not enter Eden.

The Nine Spheres of Eden

Heaven does sound great and all, but if you want to preserve your individuality and engage in open discussions about life, the universe, and everything else with the greatest minds of the ancient world, as well as from the Muslim, and possibly the Jewish, and the polytheistic traditions, I'd wager you're better off being sent to the first circle of hell. In heaven, you'll be too busy marveling at the beauty of God to get anything else done.

Dante called his work "La Comedia" not because he had a lot of jokes to tell – he had non as far as I can see, but because he saw his journey to the land of the dead as starting from a bad place (Inferno) and reaching the good one (Eden). Even still, I am reminded of a Jewish joke about the afterlife. The next world is basically a room filled with shelfs upon shelfs of books. But all of books are of the Talmud. For a person who loves to study the Torah this is heaven, for the fool who doesn't (implies the joke) - this is hell.

Some final thoughts:

1. The Avenging Poet: Dante's Divine Justice:

There is a somewhat false perception that Dante descends to Hell mainly to settle scores with the Florentines of his time—the people responsible for his exile from the city and for the death penalty that hung over his head his whole life should he return. This is a mistake. Dante is too clever of an artist to make his great poem a mere work of revenge. The fictional Dante (the narrator of the poem, also called Dante) is a round character, who starts in a certain place—in a dark forest when everything seems lost—and all through the Comedia is repeatedly exposed to his mistakes.

Dante's first significant mistake is precisely his identification, his sorrow, and empathy towards various sinners he encounters in hell. In the Canto V, Dante loses consciousness after meeting Francesca, who tells him the story of her infatuation and adultery with her husband's nephew. Dante's deep identification with the sin of passion, and with the power of reading love poems (a literary genre that Dante himself specialized in), makes him realize that maybe he himself is responsible for sending other passionate lovers to hell, like the sinful couple he talks to.

Dante faints in the Circle of the Lustful after his talk with Francesca da Rimini (‘The Whirlwind of Lovers’)

In a particularly moving moment in the Comedia, Dante bursts into tears when he witnesses the fate of the false prophets—God has turned their heads so that their tears flow through the slit of their buttocks, and they are condemned to live in some wretched pit. Virgil reprimands him for this because in the very act of identification and crying, Dante seems to be challenging divine justice.

What complicates the whole matter is that, of course, we must not forget for a moment that Dante is the one who wrote the work, and he is the one who put the false prophets in the same situation. He did follow the strict Christian framework, but he took great creative license to create and innovate within it: in the punishments for sinners, in the people he chooses to put in each circle of hell, and also later on—in his portrayal of purgatory and the division of its various levels, as well as in Eden. There awaits him his great and unrequited love, perhaps the most exaggerated crush in literature, Beatrice.

2. The first Christian depiction of hell:

The first and most authoritative account of the descent into hell (which contains a much briefer account of the blessing of the saints) was allegedly written by none other than one of Jesus' 12 apostles - Peter. Scholars generally do not believe that Peter wrote it, but it is attributed to him.

In the "Apocalypse of Peter," the Christian hell is superimposed on the Greek underworld. While I will certainly dedicate an essay to this interesting and, yes, also harrowing work, I want to point out one trope that was carried from the Greeks and the Romans: Most (if not all) literary descents to the underworld by a hero are accompanied by a faithful guide. Odysseus—the first one—had the blind prophet Teiresias as a guide. Aeneas had the sibyl Deiphobe, Peter had Jesus, and Dante had Virgil.

Thanks for reading The Library of Babel! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

1 Darkness Visible: Dante’s Clarification of Hell, by Joseph Kameen