- The Library of Babel

- Posts

- How Lolita almost destroyed my dating life

How Lolita almost destroyed my dating life

And what Nabokov answered when he was asked about Humbert Humbert and himself

I discovered in nature the nonutilitarian delights that I sought in art. Both were a form of magic, both were a game of intricate enchantment and deception.

The childhood of a lepidopterist, Vladimir Nabokov

I still remember the change in one date's face when I started talking about Lolita and why I think it's a great novel—the best I've read. While I sailed on praising the book for its style, its lyricism, and its deceptively simple plot, all my date wanted to know was why I was so interested in a book about a middle-aged man who kidnaps and rapes a 12-year-old girl. She didn't really try to masquerade her concerns.

I couldn't even tell you how many dates Lolita, the 1955 novel by Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov ruined for me. I used to secretly joke about it on my Tinder profile: "Favorite book? Not before the third date."

The accusation was never uttered overtly, but I could almost hear it in every date’s tone. Usually, and this date was not different, it came in the form of a question, what felt like a not-so-clever deflection: "Wasn't the author a pedophile? Why else would he write about that kind of story? be interested in this topic?" More likely than not, I think they were asking about me.

I don't know why I or anybody else is interested in horrific subjects, in violent stories. I'm not sure why I like romantic and sweet ones either. I suspect it's much more about the craft (which Nabokov is a master of, an absolute genius in fact) more than the subject itself. But maybe this is a cop-out. I like horror, for example, because of the possibilities it explores, the states of being it could bring the characters to experience. The horror and deep sorrow Dolly Haze experiences at the hands of the narrator are never seen directly. Lolita is not even her real name, but a nickname Humbert Humbert gave her. And it is this Humbert who tells the story, of course. He picks and chooses what to show us, but we do get horrific glimpses into her state. Into what Humbert near the end of the book calls "a garden and a twilight":

There was in her a garden and a twilight, and a palace gate - dim and adorable regions which happened to be lucidly and absolutely forbidden to me, in my polluted rags and miserable convulsions.

For years I've argued that Lolita is much more than the story of a pedophile torturing an adolescent girl for two years and hundreds of pages, until I realized that actually – this is exactly right. Sure, the book contains much more than that – it's a funny book, a shockingly funny book. It is also beautifully and marvelously written. And yet, it is all a big trap to get you, the reader, to forget what is plainly before your eyes at all times. And just like many lovers of that satanic book, I was fooled—by the narrator with his two hypnotic eyes always glowing in the dark, by the author who created him—fooled to believe that Lolita is anything more than a red and shiny poisoned apple. I never thought that it's "the greatest love story of our time" (meaning the 20th century) like Nabokov's friend, the influential literary critic Lionel Trilling so provocatively and foolishly suggested. Nabokov preferred the word "passion" and even went as far as calling Humbert Humbert a baboon who cannot control himself. But fooled I was nonetheless.

And the funny thing is, Nabokov warned us against doing exactly that. In his long years teaching at Cornell, the novelist used to open his "Lectures on Literature" course with a definition of the good reader: the good reader does not read to identify with the characters. Instead, he or she is trying to understand what the writer is doing, what journey the writer is taking us on, if we got there in the end, and by what means.

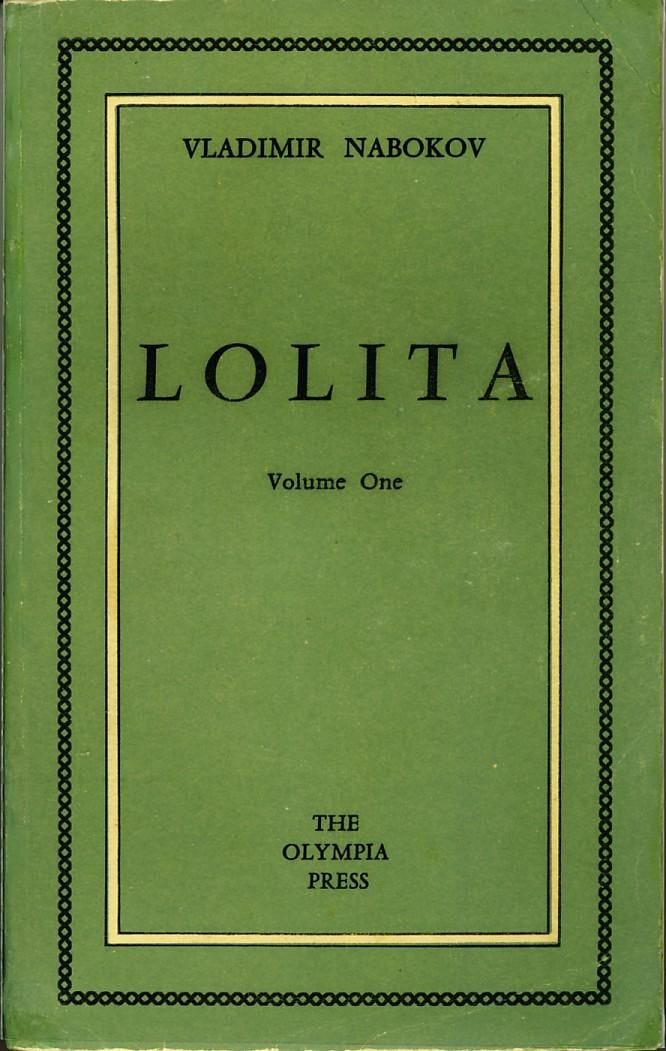

First edition cover, 1955

While I agree that this is what the good (and perhaps professional) reader should be doing, when it comes to bad reading, I see things in a slightly different way. For me—and Nabokov and his most famous novel prove the point in a wonderful and terrible way—the bad reader is first of all the one who confuses the writer with his characters. Cervantes was not mad, Don Quixote was. The same conclusion can be drawn about Nabokov, of course; we have no proof that he shared the morbid tendencies of the morbid narrator he created.

It is called Fiction for a reason, Nabokov reminds us in his opening lecture:

Literature was born not the day when a boy crying wolf, wolf came running out of the Neanderthal valley with a big gray wolf at his heels: Literature was born on the day when a boy came crying wolf, wolf and there was no wolf behind him. That the poor little fellow, because he lied too often, was finally eaten up by a real beast is quite incidental. But here is what is important. Between the wolf in the tall grass and the wolf in the tall story there is a shimmering go-between. That go-between, that prism, is the art of literature.

Nabokov called Lolita "my most difficult book," meaning the most difficult to write, but also the one whose writing brought him the most pleasure. He saw it as a huge puzzle that he had to solve. Nabokov repeatedly denied that his was a moral book—in the sense that it does not teach morality and that it does not have any clear-cut message. A statement that is closer to an Oscar Wilde-esque evasion than to the truth. He also refused to answer silly questions like, "What do you and Humbert Humbert have in common?" (Another way of asking, "Are you, Mr. Nabokov, a pedophile too?") In an interview on American television, Nabokov provided probably the most ingenious evasion ever to come out of a writer's mouth.

Speaking about Humbert Humbert, Nabokov said:

Of course, he is a European and a man of letters as I am, but I have been very careful to separate myself from him. For instance, the good reader will notice that Humbert Humbert confuses hummingbirds with hawkmoths. Now I would never do that, being an entomologist.

To me, the real tragedy of Lolita—aside from that of the fictional character of Dolly Haze—is that despite the fact that Nabokov intended to provide us with an extraordinary glimpse into the loathsome mind of a murderous pedophile, what popular culture has chosen to take from this wonderful and terrible book is the false and very troubling image of Lolita, the seductive girl.