- The Library of Babel

- Posts

- Unless you're a devout Christian, you should really stop using the term 'The Old Testament'

Unless you're a devout Christian, you should really stop using the term 'The Old Testament'

There's a better, much more accurate name for this canon of 24 amazing books

Unless you're a devout Christian, you should really stop using the term 'The Old Testament'

Melito of Sardis, a bishop from the second century C.E., was the first Christian writer to refer to the Hebrew Bible as the Old Testament. His point wasn't simply to say that the 24 books which stood at the center of the Jewish scriptures were older than the books of the New Testament (though they obviously were) but that the old covenant between God and his chosen people was null and void. With the coming of the messiah there is a new covenant to take its place, the one that Jesus brought with him down to earth.

If you're a devout Christian seeing the world through the lens provided to you by Paul, this framework probably makes sense to you. For the rest of us, it's time to reconsider our terminology.

So, let's discuss it.

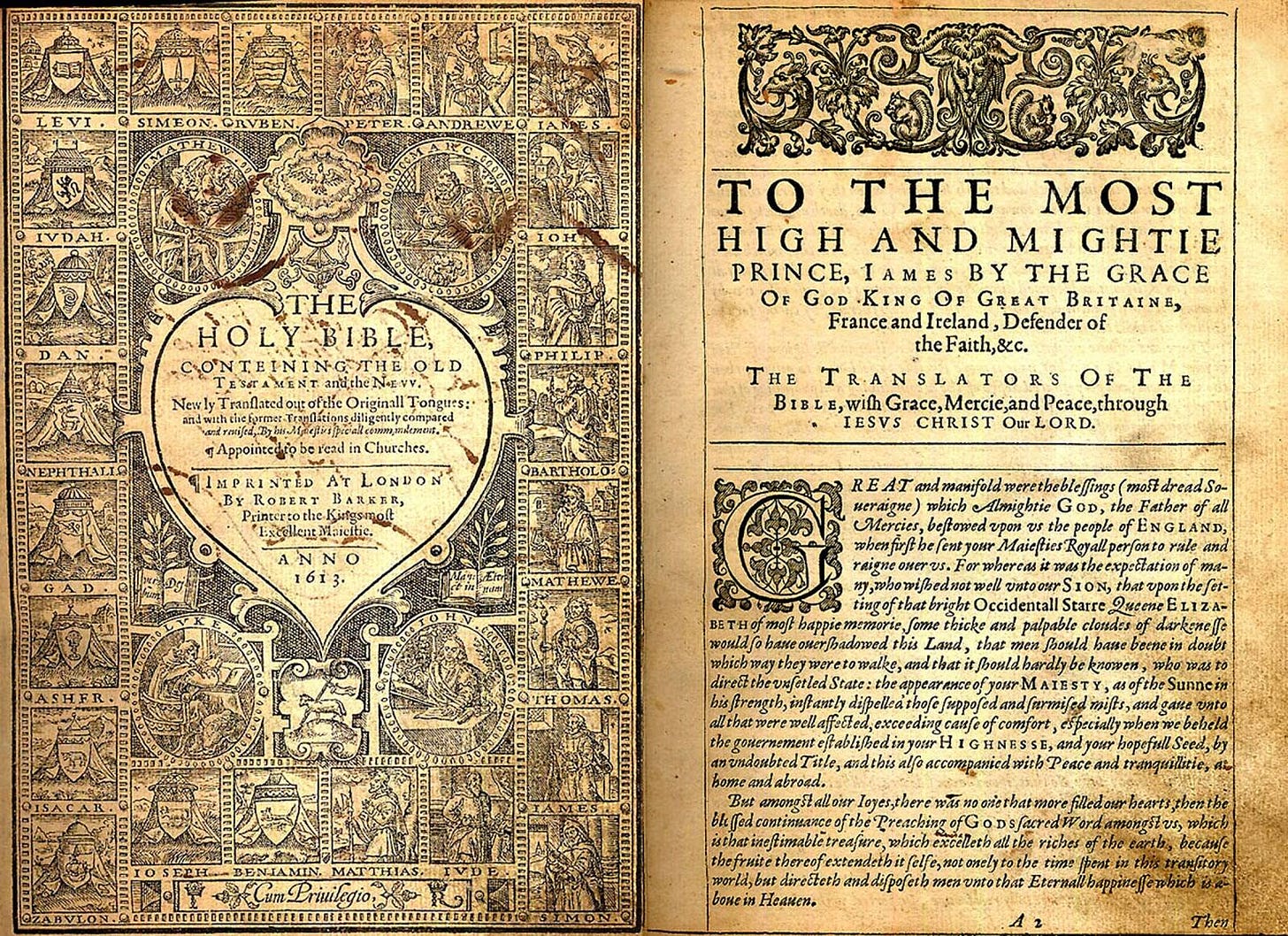

“The Holy Bible contain the Old Testament and the New”, the first print edition of King James Bible

Brushing up on my New Testament, especially the four gospels, I was reminded by Jesus' insistence that he did not come to oppose the Jewish law, but to vigorously uphold it. Throughout his short life, Jesus took issue not with the law of the Torah, but with what he saw as a false interpretation of it by those in power. He preached against the hypocrisy of the powerful, who might rigorously follow their own harsh understanding of God's commands but neglect to see the suffering of the people they are supposed to serve and care for.

As Rabbi Akiva famously said, the whole of the Torah (the Hebrew name for the Hebrew Bible) could be summed up in just one sentence: "Love Your Neighbor As Thyself." I feel confident enough to argue that Jesus would probably agree. He said as much in Matthew 22.

Throughout his life, Jesus interpreted the commands of the Torah in a more allegorical manner. It's no wonder that his early followers, all Jews, referred to Jesus by the Hebrew word for teacher—Rabbi.

It wasn't until Paul emerged on the scene and propagated the idea that what is most important is the life and death of Jesus, surpassing even his teachings, that the concept of a New Testament, a new covenant with God, emerged. While Jesus' teachings remained significant, the focus shifted to his sacrificial death for the sins of humanity.

From this perspective, the stories of the Hebrew Bible could be interpreted as signs and symbols foreshadowing and perhaps even following in the future footsteps of Jesus' life, death, and resurrection—as even time itself could not contain or limit God’s plans.

While Jesus' first followers were Jewish like him, as time went by more and more of the so-called Gentiles converted to the new faith. As the ranks of Christianity grow steadily, if slowly, in the first century or so after the death of Christ, the Jewish religion—which was respected by the Greeks and Romans as an ancient faith—came to be looked at with contempt. The people of Israel turned their backs on the Messiah (didn't they?), and now his true followers should create the new people of Israel by seeking out converts.

So much blood has been spilled because of this interpretation. So much missed opportunity for a true and inspiring dialogue between the two sister religions. But what are we still missing by designating 24 of the most influential books in Western culture to a place of mere relics of an ancient era?

Using the loaded term ‘Old Testament’ relegate the Hebrew bible to a position of outdated truth at best, and to a false and evil lie at worst, as seen in certain Gnostic interpretations. It's clear that the writers and editors of the Hebrew Bible did not have a newer, better book in mind as they composed their own.

Viewing every story in the Hebrew Bible as a prefiguration of Christ is like studying the Homeric Poems only to understand Virgil's Ennead. Obviously, you can do that, but then the stories Homer has to tell us, and so beautifully, no longer stand on their own.

I think that the same thing happens when we treat the Hebrew Bible as the Old Testament: the wisdom and the poetry are pigeonholed to one set of accepted interpretations.

We've moved away from using A.D. (Anno Domini – the year of our Lord) and B.C. (Before Christ) in favor of the more neutral Common Era (CE) and Before Common Era (BCE). Yet, many of us still cling to the term the ‘Old Testament.' This isn't exclusive to Christian believers. Ever since I started writing in English about theology, I've noticed that the use of this term is not just prevalent but almost automatic.

When a term is so popular that it become transparent, even the people who should know better—scholars of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament—persists in using it, perpetuating outdated stereotypes of the Jewish people as stubbornly resisting the Christian teachings.

Moses receiving the Torah at Sinai. The houses in the background are hilarious

Now a serious response to my whole argument would be to note that the Hebrew Bible and the Old Testament are not entirely synonymous. Different Christian denominations have canonized varying collections of books from the Jewish writings available to them. While all include the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, some also incorporate additional texts from the Jewish Apocrypha. However, even respected Bible scholars like Bart D. Ehrman often use the terms 'Hebrew Bible' and 'Old Testament' interchangeably, blurring this distinction.

There exists a view within Judaism that Israel is a nation that stands alone—an idea I find not only incorrect but morally troubling. Jews, like people of all cultures, have learned from the diverse cultures, religions, and peoples they encountered throughout history. Cultural and religious chauvinism is not the path forward.

Consider Islam, for instance. While it's evident that the Quran is influenced by Jewish and Christian stories, the exchange of ideas is reciprocal. We can't truly imagine a thinker like Maimonides (1138–1204), arguably the most significant Jewish philosopher in history, without considering the philosophical thinking of prior Muslim thinkers he studied and read, who in turn drew from ancient Greek philosophy. Maimonides even wrote his renowned work, 'The Guide for the Perplexed,' in Arabic—the philosophical language of his time and place.

I want to stress again: I have no issue with how Christians interpret the Bible—it's an integral of Christianity, and its impact on Judaism is immense. Consider this: the meaning of many Hebrew words from the Bible have shifted in modern Hebrew due to influence of the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. For example, 'Nephilim' (Gensis 6) means ‘giants’ in modern Hebrew, derived from the Greek translation. The original meaning was probably something like: Those who fell down (the Hebrew word Liphol is to fell down). Similarly, Tohu wa-bohu (תוהו ובוהו)—which is how the book of Gensis describe the state of the world before Creation was reinterpreted to mean the Greek 'chaos'.

While our perspective often aligns with the Christian viewpoint, the potential interpretations of the Hebrew Bible are as boundless as human creativity. Understanding the literal meaning of the text, as far as possible, is crucial, as is recognizing the vast ocean of interpretations shaped by those who compiled the corpus of these 24 books. It's essential to remember that these are distinct works, written and edited across centuries upon centuries.

Some derogatory terms can be appropriated and given new contexts. Jews and Christians came to be known in Muslim territories as the peoples of the book. This was no compliment, but a way to chide both peoples for not accepting Islam because of blind adherence to their own misguided Books. It is only much later that Jews adopted this term wholeheartedly to mean – the people who gave the world the book of books: the Bible.

I don't believe that 'The Old Testament' can be appropriated in the same way. Fortunately, there is a much better alternative, which incidentally is also the correct one: just call it what it is, 'The Hebrew Bible'.

Thanks for reading The Library of Babel! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.