- The Library of Babel

- Posts

- You can't get any more modern than Kafka

You can't get any more modern than Kafka

What do we talk about when we talk about Franz Kafka and the Kafkaesque

1.

You know you made it as an artist when there's an adjective craved from your name. Merriam-webster dictionary define Kafkaesque as "having a nightmarishly complex, bizarre, or illogical quality". The example provided is "Kafkaesque bureaucratic delays".

Just as people in the Middle Ages didn't know they were living in the supposedly dull millennium wedged between the Ancient World and the Renaissance, Kafka had no inkling that his work would come to be described as 'Kafkaesque.' When the 36-year-old Franz Kafka finally penned a letter to his father, Hermann, detailing years of parental abuse, the word 'Kafka' evoked a different feeling within him. For the writer, his father's last name symbolized strength, while Löwy – his mother's side of the family – was where he claimed to have gotten all his weaknesses and his frightened disposition.

2.

Throughout the 42-page letter, the figure of Hermann Kafka is revealed to be that of a strict and cruel father. Yes, Hermann worked hard all his life to support his family, but his harsh, all-knowing character prevented any possibility of empathy from his children.

For Franz, Hermann's eldest child, one incident from childhood spent in the shadow of the domineering father, transcended all others. The young Franz Kafka was “whimpering for water”, admittedly with the partial intention of annoying his parents and amusing himself. His angry father then proceeded to uproot him from his bed and lock him out on the balcony in the freezing Czech winter. This traumatic experience made it clear to the child that, at any moment, he could be taken from his comfortable surroundings and thrown into a cruel, lawless world.

While this may seem like the quintessential Kafkaesque moment, the key element that is repeated again and again in his fictional writing—from Josef K.’s encounter with the law to Gregor Samsa’s sudden realization upon waking that he has turned into a “monstrous vermin” in his bed—I aim to reveal another dimension of Kafka's writing. Or perhaps, another side of the same coin.

3.

August 28, 1904, Kafka wrote in a letter to his friend Max Brod:

When I opened my eyes after a short afternoon nap, still not quite certain I was alive, I heard my mother calling down from the balcony in a natural tone: "What are you up to?" A woman answered from the garden: "I'm having my teatime in the garden." And I was amazed at the resolute way people live their lives.

4.

In the first of only two slim volumes of stories Kafka published during his lifetime, there lies a short story titled 'The Men running past'. In three short paragraphs, Kafka unveils the profound mysteries embedded within everyday life. In this short story, the narrator tells of a night walk he took on one of the streets of his city when all of a sudden, he noticed a man running in the opposite direction to him, and a few seconds later—another man running behind the first and shouting something.

Contrary to what might be expected of him, the narrator refrains from intervening. Instead of chasing the two down, he provides us with his various considerations against acting: First of all, it is night and the moon shines beautifully and attracts his attention. Besides, couldn't it be that the two men arranged the chase for their own pleasure? Maybe they are running after a third person, or the second runner intends to murder the first one and we will be complicit in the act, or the two are not connected in any way and each one runs to his bed. They both could also be crazy, or maybe, just maybe, the one of them has a weapon? Finally, the narrator redeems himself by saying that he has the right to be tired, that he drank quite a bit of wine this evening, and in any case, as soon as the second runner is gone, he already feels satisfied.

Interestingly enough, we find among Kafka's papers a drawing he made of three runners. And so now it is our turn to ask: If we conclude that the narrator of this enigmatic tale did not in the end become entangled in the pursuit, who is this third person who is chasing after the two? Or are they all running in the same direction but are separately trying to reach different locations?

5.

I should so like to be able to draw. As a matter of fact, I am always trying to. But nothing comes of it. My drawings are purely personal picture writing, whose meaning even I cannot discover after a time.

Conversations with Kafka by Gustav Janouch

In his first year at university, Kafka discovered a talent for drawing.

Disinterested in his law studies, he opted for courses in art, architecture, and philosophy. At this early juncture in his life, Kafka had yet to envision himself as a writer. Between his two great passions—visual arts and literature—it appeared that the former might win out. He discovered, to his surprise, a not insignificant talent for drawing, and he began filling the margins of his notebooks with doodles.

Reiner Stach, author of a monumental, three-volume biography of Kafka, suggests that the student’s first sketches represent an initial, yet major step in the crystallization of his future literary creativity. And indeed, in those sketches he made, those rudimentary drawings, we find almost a mirror image of his literary writing. Kafka's characters seldom resemble fully fleshed-out individuals; rather, they seem to embody a gesture, lacking clear beginnings and known ends (except when they die, which can happen on occasion).

6.

For me, Kafka embodies the essence of the modern condition. Not necessarily the nightmarish bureaucracy that encroaches upon society, stripping away autonomy and freedom, but rather the embodiment of our contemporary ignorance. His stories reflect our struggle to determine what actions we should take in the face of ambiguity, leading to a paralysis born from the perpetual elusiveness of truth. And it's not because truth is inherently absent. There may very well be a solution to the enigma of the two runners. Yet, it remains perpetually out of reach. Why? maybe, in some unspoken manner, it's morally objectionable to reach a solution. Maybe in taking a definitive stance you risk condemnation, tarnishing your reputation irreparably.

Another possibility, which seems more reasonable to me (when dealing with Kafka, everything must remain in the realm of possibility)—is that the main thing is observation. This is the name of the first collection of stories he published in his life: Betrachtung, which can be translated as either "Observation" or "Contemplation."

Kafka doesn't do mimesis – he does not create an imitation of reality in his writings. There is only observation of it. An observation that has no understanding attached to it.

"We tell ourselves stories in order to live", writes Joan Didion at the start of her seminal essay on the Sixties (The White Album). Kafka didn't tell stories in order to make sense of the world—I don’t think he told them to confuse it either. He does not teach us how to live. He "only" shows us how he perceives the world. And if the world is incomprehensible, then incomprehensible parables are the necessary thing we lack, right?

7.

Kafka on parables:

Many complain that the words of the wise are always merely parables and of no use in daily life, which is the only life we have. When the sage says: "Go over," he does not mean that we should cross to some actual place, which we could do anyhow if the labor were worth it; he means some fabulous yonder, something unknown to us, something too that he cannot designate more precisely, and therefore cannot help us here in the very least. All these parables really set out to say merely that the incomprehensible is incomprehensible, and we know that already. But the cares we have to struggle with every day: that is a different matter.

Concerning this a man once said: Why such reluctance? If you only followed the parables you yourselves would become parables and with that rid of all your daily cares.

Another said: I bet that is also a parable.

The first said: You have won.

The second said: But unfortunately only in parable.

The first said: No, in reality: in parable you have lost.

Translated by Willa and Edwin Muir

8.

Kafka's letters and diaries. This is where we should go in search of the man behind the undeciphered parables, the absurdist stories (I almost wrote: “the real man behind the undeciphered parables, the absurdist stories”).

In the many, many letters he wrote, we come across the raw Kafka, not yet polished into literature. Frequently, we stumble upon sentences that stretch longer and longer, laden with the awkwardness and occasional ambiguity of their phrasing.

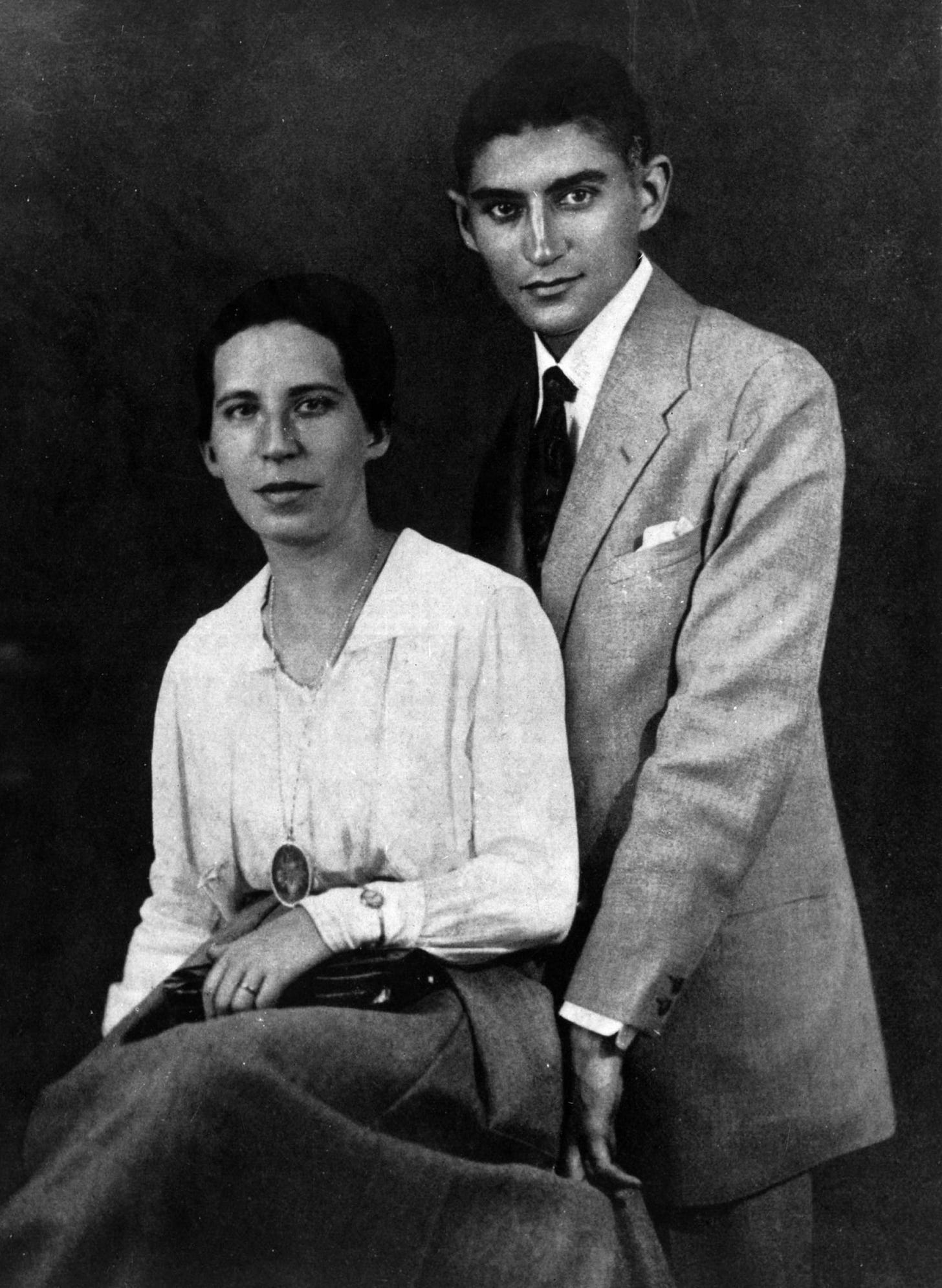

Of course, it's tempting to idealize Kafka by turning him into a new kind of saint, the post-modern kind. In letters to Felice Bauer, his first fiancée, he tried to present himself as neurotic as he possibly can in order to keep her away. He may have initially felt a glimmer of happiness because "the door between us is starting to move", but continues to warn her over and over again that he is a man who cannot be trusted.

In a slightly odd and voyeuristic way, there is something heartening to discover Kafka using the same pathetic techniques that are familiar to anyone who has once been a young man with a deep-rooted fear of commitment (the position is painfully familiar to read).

9.

I strive to know the entire human and animal community, to recognize their fundamental preferences, desires, and moral ideals, to reduce them to simple rules, and as quickly as possible to adopt these rules.

Kafka to Felice Bauer

10.

A typical Kafka story resembles a labyrinth filled with spiraling staircases and countless false doors, where an ironic twist lurks just a step or two in front of you. In a diary entry dated June 25, 1914, Kafka recounts a sleepless night when he was visited by an angel. Startled, he lowered his gaze and prostrated himself, pondering what to ask the divine being before him. Alas, the angel proved to be nothing more than a figment of his imagination.

It was no living angel, only a painted wooden figurehead off the prow of some ship, one of the kind that hangs from the ceiling in sailors' taverns, nothing more.

Translated by Martin Greenberg with the cooperation of Hannah Arendt

11.

In The World of Yesterday (Stefan Zweig, 1942) there was knowledge. In Kafka's world, there exist only possibilities. Not even compromises, just hollow possibilities.

12.

Kafka is the hopelessly undecided. And the highly publicized legal battle (at least in the country where I live, and for a former employee of the National Library of Israel) regarding the question of whether his writings should go to that national library or to the Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach (German Literature Archive Marbach) is not a battle that would have been too foreign to the man himself. In the postcard he sent to Felice Bauer, he recounts two contrasting reviews of his recently published story "The Metamorphosis."

One review saw the story of Gregor Samsa turning into a giant insect as an example of his "rooted German" writing, while the other—authored by Max Broad— viewed the story as a quintessential "Jewish document of our time."

Kafka asks Felice to "tell me who am I really". But this is just another ironic gesture on his part. Kafka himself remained uncertain about his identity and avoided making definitive decisions. Was he Jewish? He didn't go to synagogue, nor believe in the God of the Hebrew Bible. Was he Czech? He was writing his literary works in German, which was his native tongue. Was he German? He was living in Prague ("This little mother has claws", he wrote of his native city to another friend, Oskar Pollak in 1902).

13.

Even since he decided to be a writer Kafka grappled with a profound question: What are stories, and what unique power do they hold? He found a crucial insight into their potency in the Jewish Hasidic tales he avidly read and admired. From these pierce mystical Jewish tales he learned that true stories are not mere entertainment, but a way to one's soul and heart. Rabbi Nachman, the great Hassidic storyteller believed stories, if told correctly, could even mend the broken world we inhabit.

This is Kafka writing to Oskar Pollak:

I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound or stab us. If the book we're reading doesn't wake us up with a blow to the head, what are we reading for? So that it will make us happy, as you write? Good Lord, we would be happy precisely if we had no books, and the kind of books that make us happy are the kind we could write ourselves if we had to. But we need books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us. That is my belief.

14.

Kafka wasn't a mystical writer in the sense of seeking unity with God. His bursts of wonder are experienced always with the world at large. You can sit peacefully at home, warming up next to the fire with your family beside you, and then something—a feeling, a yearning — grips you, compelling you to step out onto the bustling street, amidst its vibrant lights and unfamiliar faces, only to find yourself once more at another friend's house (“The Sudden Walk”). It's a journey from order to chaos and back to order again.

15.

Kafka was also Greek in a deep sense. Plato’s allegory of the cave is the place where Kafka lives. It's also where we live. The difference is that he knew and acknowledge that.

16.

The most non-Kafkaesque character we could find in modern culture would be a character from a Hayao Miyazaki film: a protagonist with a solid and decisive personality, with fixed goals and unwavering moral compasses. This is a major part of the charm of the beloved characters we find in "Princess Mononoke", "Spirited Away" and more.

17.

Vladimir Nabokov, an ardent admirer of Kafka, suggested that Kafka may not have realized it himself, but the insect Gregor Samsa transforms into at the beginning of "The Metamorphosis" is actually a large beetle. Which means that if he wanted, Gregor could fly out of the open window of his room and find himself a new warm home and with plenty of food in the dirt...

Curiously enough, Gregor the beetle never found out that he had wings under the hard covering of his back.

Jorge Luis Borges, another fan, saw Kafka as the epitome of the writer who creates his own literary tradition. In his essay titled "Kafka and his precursors", Borges gives the example of a Chinese fable by Han Yu, a prose writer of the ninth century, which describes the unicorn. A unicorn in Chinese mythology is "a creature that cannot be classified... so we could be in the presence of a unicorn and not know with certainty that it is one."

Meaning, much like Lovecraft's monstrous creations (albeit in a more prosaic and everyday context—Kafka being the master of the everyday), Kafka's creatures defy classification. In his only story overtly featuring Jewish themes, "In Our Synagogue," there's an unidentified rodent residing within the synagogue of a "little highland town." While Kafka emphasizes the creature's harmlessness, its presence in a sacred space is inherently disquieting to readers. What is this creature a symbol of? We never figure it out.

If communication with the animal had been possible, then we would have been able to offer it the assurance that the community in our little highland town is shrinking by the year, and is already having difficulties finding the funds to keep up the building. It is quite possible that in a while our synagogue will have become a granary or something of the sort, and that the animal will find the peace it so painfully lacks now.

Translated by Michael Hofmann

18.

The fact that Kafka never finished any of his three novels is no surprise. not to me. His best works are short. When he ventures into longer plots, they often falter, with the illogical veering into the realm of the absurd—not in a philosophical sense, but sometimes in a downright silly manner.

Consider the opening line of "The Trial": “Somebody must have slandered Joseph K., for one morning, without having done anything wrong, he was arrested.” This line establishes a world unto itself. Pushing further risks destabilizing the entire construct, and indeed, a few chapters into the novel, the narrative collapses.

What's happening to Joseph K.? In contemporary terms, we might say he's being "canceled", abruptly thrust into a trial without ever being presented with the accusations against him, no matter how vigorously he searches. The plot crumbles because the attempt to depict his trial encounters an insurmountable barrier.

This is why I regard Kafka as the artist of brevity, the master of omission. The more words he employs, the more precarious the tightrope he treads becomes, inevitably leading to its snapping.

19.

In Max Brod's biography of Kafka, he recounts an incident when he and a group of friends gathered to listen to Kafka read the first chapter of "The Trial." Despite the harrowing nature of the narrative, Brod observed that everyone in the room felt an uncomfortable sensation, as if something was tickling them, prompting an inexplicable urge to laugh.

20.

While most of his stories does not deal with the naked, faceless power of the modern state (Not as much as most of us automatically assume), I do feel that the point of view of a Kafka story is almost always one of an adult who, as a child, was taken out of his secure bed in the middle of the night and thrown to the balcony to freeze. Confuse ever since, unsure of himself and his reality (which is always a convention, isn't it?)—he is asked to navigate situations that can be absurd or terrible but can just as easily be ones that most find no trouble navigating. This outlook can equally be one of wonder, just as much as it can be one of terror.

For we are like tree trunks in the snow. In appearance they lie sleekly, and a little push should be enough to set them rolling. No, it can't be done, for they are firmly wedded to the ground. But see, even that is only appearance.

21.

Through the passage of time and extensive research, Kafka—who died in 1924 at the age of 40—has become more of a symbol than a person who lived and wrote in the first half of the 20th century.

A Kafka scholar once counted 150 separate schools of interpretation in the study of Kafka and his work. Not 150 books, 150 schools of thought. Which makes me think I might have committed a terrible error by writing this essay. Kafka refused to define who he was, so why should we do it for him?

Thanks for reading The Library of Babel! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.